Born and raised in a Jewish household in Massachusetts, Alpert saw himself as an atheist. His first real brush with spiritualism, however, came much later:

“I didn’t have one whiff of God until I took psychedelics.”

A severe stroke in 1997 paralyzed Ram Dass on the right side, which left him unable to speak for a while. He also underwent hip surgery after a fall in 2008. All these brushes with mortality led him to comfort his followers in a videotape:

“I had really thought about checking out, but your love and your prayers convinced me not to do it… It’s just beautiful.”

Be Here Now

Ram Dass was celebrated for his pioneering spirit. Together with Timothy Leary, he started projects in which prisoners (and dying patients alike) were granted a second chance with psychedelics.

He also wrote about his experiences with drugs, most notably in his 1971 book, “Be Here Now”, which he wrote after his trip to India.

“I want to share with you the parts of the internal journey that never get written up in the mass media… I’m not interested in what you read in the Saturday Evening Post about LSD. This is the story of what goes on inside a human being who is undergoing all these experiences.”

Ram Dass also wrote books on selflessness, namely “How Can I Help?” and “Compassion in Action”. He also taught his fellow baby boomers not to fear old age, with the book “Still Here: Embracing Ageing, Changing, and Dying”.

In the 60’s, Alpert became rather like the ‘uncle’ of the psychedelic movement, a friendly face, showing people where they could go. He travelled east, where the sparks of spirituality burned even brighter.

“Now the baby boomers are getting old… and I’m learning how to get old for them. That’s my role.”

Rite of Passage

The electric boom of LSD and other psychedelics in the late 1960’s can be, in part, traced to Alpert and Leary’s experiments at Harvard.

As a young psychology professor, Alpert co-led The Harvard Psilocybin Project, and gave magic mushrooms and LSD to prisoners, professors, and students to see their effects.

Ram Dass later recalls that he first tried psilocybin in Leary’s living room:

“I peered into the semidarkness and recognized none other than myself in cap and gown and hood. It was as if that part of me, which was a Harvard professor, had separated or dissociated itself from me.”

New York, New Delhi

After their LSD experiments got Alpert and Leary kicked out of Harvard in 1963, they continued their efforts in an old New York mansion. The place soon caught the attention of Beat Generation icons, such as Jack Kerouac, William Burroughs, and Ginsberg.

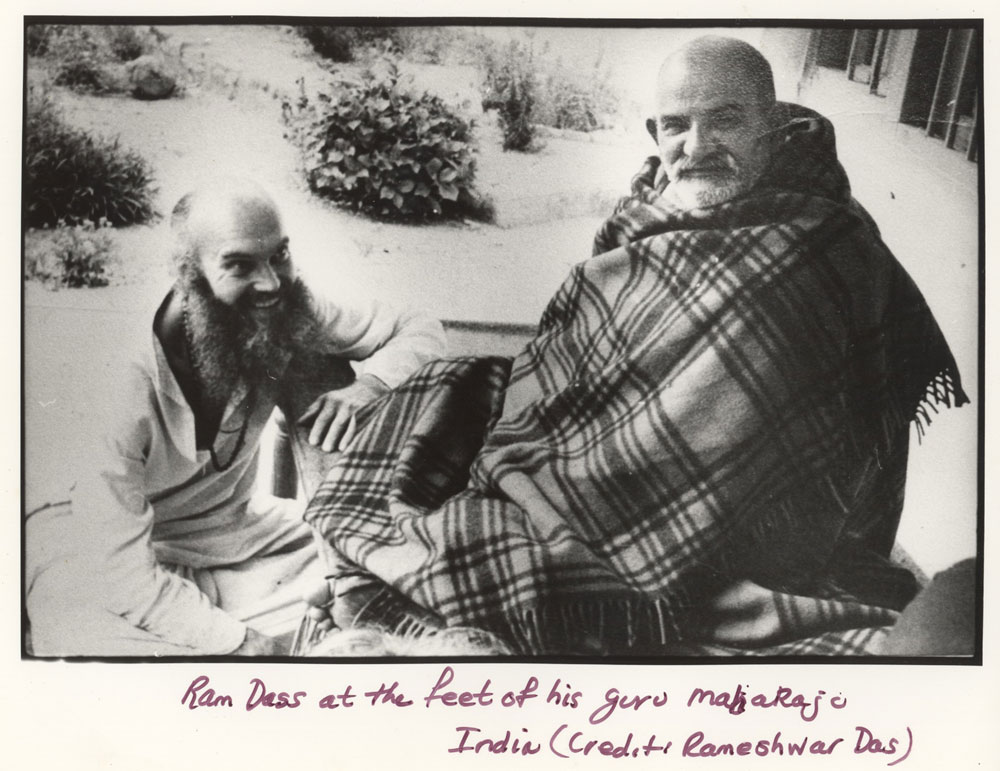

At Ginsberg’s behest, Alpert set out for India in 1967 in an effort to seek “true enlightenment”, one that doesn’t rely on drugs. There, he met Neem Karoli Baba, who would later become his guru.

Neem Karoli Baba gave Alpert a new name: “Ram Dass”, which means “servant of God” in Hindi. The psychologist then learned all about yoga and meditation, and the tenets of Buddhism and Sufism.

Later Years and Legacy

Upon returning to the States, Ram Dass began writing “Be Here Now”. This was also a period that saw him turn away from drugs:

“I don’t want to break the law, since that leads to fear and paranoia.”

Further projects included the Hanuman Foundation in 1974. Most notable was the Prison Ashram Project, which aimed to give prisoners a way out via spirituality.

His Seva Foundation also works to prevent blindness in developing countries, while his Love Serve Remember Foundation aims to preserve his teachings (and those of his guru).

The first retirement years of Ram Dass were spent in the quiet town of San Anselmo, California. Scattered within his home were statues of Buddha, prints by Japanese artisans, and seashells from trips well-spent.

Afterwards, he moved to Woodside, California, then to his final home in Maui. As for the physical and spiritual suffering caused by his 1997 stroke, Ram Dass said:

“It’s brought out new aspects of myself and aspects of my relationship to the world. The stroke has gotten me into a stage of life… this is a stage close to death, a stage which is inward.”

Ram Dass began his final lecture tour after regaining his speech, starting with profound realizations on his state of “heavy grace”.

“All illnesses are part of the passing show. You are not just your body. You are the witness of your body.”

Rest in peace, Ram Dass. You are gone, but not forgotten.

(For a deeper dive into the life of psychedelic hero Ram Dass, check out this blog.)